At age 45, Jean-Pierre Wolff felt married to his job. Ten years prior, he’d co-founded a startup in electrical engineering field services that was later acquired by Emerson Electric. He’d also earned a Ph.D. in electrical engineering and applied technology and an MBA while working full time. “I was hiding in my studies,” Wolff says. For over 20 years, he’d built a very successful career in business and engineering, but his teenage interest in agriculture, a track he first pursued in college, still called to him to make a midlife career change.

“You can have a very successful career, but it’s not always truly what you really wanted to do from the very beginning,” says Wolff, owner of the certified sustainable Wolff Vineyards. “As the years go by, people tend to become risk averse.”

Wolff, whose father is French and mother is Belgian, moved from Belgium to San Francisco when he was 21 to complete a degree in electrical power engineering. While Wolff planned to return to Europe to work, life took him in a different direction.

“When you are part of the million-mile flyer club, and it’s not because of credit card points, you begin to reflect on what matters,” Wolff says. Sitting in first class on one of his many flights for work, Wolff reminisced about the pineapple and cotton plants he’d grown as a teen in his childhood home.

How to make a successful midlife career change

Wolff decided to buy a vineyard in the late ’90s—but not without certain prerequisites to guide his decision. “I did a matrix decision process,” he says. He wanted a vineyard near the ocean and a culturally rich university. It also had to be in an up-and-coming appellation and, ideally, part of a working farm to diversify his portfolio. In San Luis Obispo, California, the coastal and fertile Edna Valley appellation checked all the boxes. After much research, Wolff discovered that he could get the same price point for an ultra-premium chardonnay in the Edna Valley as one in Napa, and the land was much cheaper.

His new home was a 125-acre vineyard on a working farm 4.5 miles from the Pacific Ocean and minutes from downtown San Luis Obispo. The vineyard was owned by a mechanical aeronautical engineer and wine was made by an Italian metallurgical engineer (someone who safely transforms metals into useful products)—two friends who’d met working together in Pasadena’s aerospace industry. For Wolff, an electrical engineer, the transition seemed fitting.

Today, Wolff Vineyards is a well-respected family-owned vineyard and winery, thanks to help from his wife Elke’s CPA background and their two sons, Clint and Mark. (Currently, Clint is the tasting room/events manager, and Mark is an assistant winemaker.)

Anticipate challenges

While Wolff didn’t start a vineyard from scratch, he says it was a fixer-upper that required a lot of work. “The first few years, you may have to tighten the belt and be able to financially take a hit and still make it through,” he says. For Wolff, those challenges included 9/11, the dot-com bubble burst, the Great Recession, COVID-19 and a historical drought.

“I would never want to be the one inventing a time machine because I don’t want to know the future,” Wolff says. He believes a person orchestrating a midlife career change must take a calculated risk. “There’s a difference between being a risk-taker and a gambler,” he says. “It’s fine to have a dream. But the dream also has to have a reality check, so you don’t set yourself up for failure.”

He did, however, prepare himself for the unknown future.

Seek mentorship

In addition to taking not-for-credit classes on viticulture and winemaking at the University of California, Davis, Wolff familiarized himself with the industry by asking questions. “I actually picked up the phone and talked to two of the biggest consulting firms associated with vineyards and wineries,” he says. He asked principals at these think tanks questions to understand the historical economics of different appellations, wine industry trends and vineyard financing.

Wolff wanted to learn the small, handcrafted winemaking process, so he asked Romeo Zuech, his vineyard’s former winemaker, to mentor him for a couple of years. The first year, Wolff was the student and took notes (that he still has) as he watched Zuech make the wine using traditional European techniques. The second year, Wolff made the wine. He says he’ll never forget the moment Zuech tried his first pinot: “He swirled it and put his nose in it. I was having heart palpitations…. Then, he looked at me and said, with his thick Italian accent, ‘Jean-Pierre, not bad for a Frenchman.’”

Be open-minded about your midlife career change options

With winemaking and farming, every year is different. Particularly with the impact of climate change, Wolff said he has to be open to adjusting how he does things each year.

“It was basically a blank canvas for me,” he says. “I didn’t come with preconceived notions about the do’s and don’ts in farming.” In fact, he took an unconventional approach to viticulture by involving environmental regulatory agencies some farmers avoided.

“This is a special piece of land. I’m really only a steward of the land here. My title on the property 200 years from now won’t mean anything,” says Wolff, the vicechair for the California Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board.

Wolff collaborated with fish and wildlife agencies to begin migratory stream restoration and welcomed the local university, Cal Poly, to use his land for research. These biologically integrated farming systems projects helped develop techniques to naturally fight disease and use fewer pesticides. They introduced ladybugs to fight aphids and wasps to attack mealy bugs.

His vineyard became known as a living laboratory. “Once an engineer, always an engineer,” says Wolff, who frequently holds local university classes at the vineyard.

Think positively

One of Wolff’s favorite mantras is, “I’m going to turn lemon juice into lemonade.” By combining his curiosity, analytical mind and love for the environment, Wolff has proven how successful an engineer can be at turning grapes into award-winning wine.

For Wolff, the glass is never half full. It’s three-quarters full. “It has always served me right to have that positive thinking because that helps your emotional bank account when you… have to make a withdrawal,” he says. “And at least you have something left in that emotional savings account… if you have a positive outlook on life.”

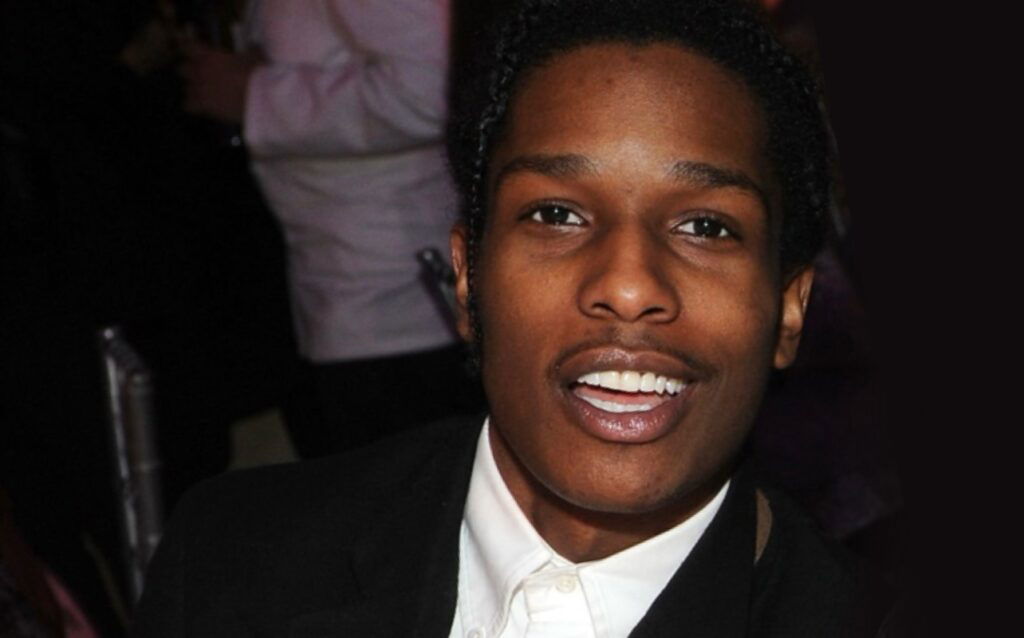

This article originally appeared in the September/October 2024 issue of SUCCESS magazine. Photo by Shannon McMillen/courtesy of Wolff Vineyards.