Alopecia, a general term used to describe hair loss, impacts Black women disproportionately. Nearly half of all Black women will experience some form of hair loss in their lives. It can come in a variety of forms, including one of the most commonly known as alopecia areata. Famous women who live with alopecia include Jada Pinkett Smith and “Summer House: Martha’s Vineyard” star Jordan Emanuel.

Treatments can vary depending on the cause and range from topicals to ointments to even treatments involving stem cells. These treatments can be expensive and largely paid for out of pocket. One Black dermatologist at Johns Hopkins may have just stumbled upon the solution: diabetes medication.

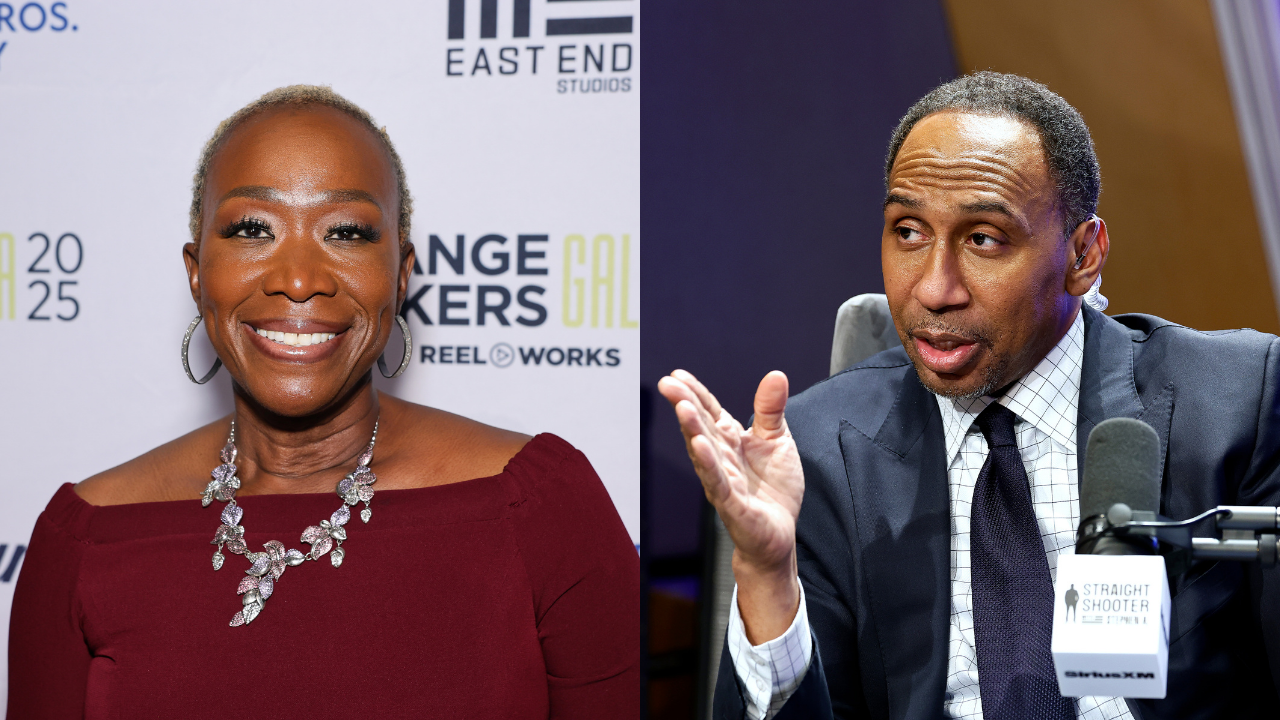

Dr. Crystal Aguh, a dermatologist and director of Johns Hopkins Medicine’s ethnic skin program, has had major breakthroughs in her research on the low-dose oral diabetes medication metformin’s effect on reversing hair loss.

The drug, a non-insulin medication used to help manage blood sugar levels, also has components that can target or slow the scarring that can happen to a diabetic’s organs. Previous research by Aguh showed that insulin resistance was also a factor in scalp scarring.

“We had to give women a better chance to get their hair to grow back,” she told the Baltimore Banner in a recent interview.

Administering a low-dose cream version of the drug directly to the scalp, she tested a series of 12 Black women who all had central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) — one of the most common forms. She found that nine patients improved their scalp scarring, and six patients had “clinical evidence” of hair regrowth after the first six months.

“Low-dose oral metformin may reverse the fibrotic transcriptional signature in CCCA and promote hair regrowth, suggesting its potential as a targeted therapy for this scarring alopecia,” she wrote in her findings published in JAMA Dermatology.

Recommended Stories

What’s needed next for Aguh’s research is formal clinical trials where the treatment will be tested for the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval. Should this drug become approved by the FDA, it could be life-changing for many people, Black women especially.

According to Aguh, up to 15% of African-American women suffer from CCCA alone. Speaking to the outlet about the impact hair loss can have on a person, she said, “Devastating is an understatement.”

She added that beyond beauty and self-esteem, roughly 10% of women will delay or refuse critical care that could lead to hair loss, like chemotherapy.

It’s not fully understood why Black women are so prone to hair loss and developing alopecia. Writing in an article published by Hopkins, Aguh said, “Unfortunately, certain types of hair loss are genetic, and very little can be done to prevent them. Genetic types of hair loss include alopecia areata and female pattern hair loss.”

She added that other forms of hair loss can be caused by stress, poor diet, and styling.

“Black women, in particular, are prone to a type of hair loss called traction alopecia, which is caused by heat, chemicals and tight styles that pull at the hair root, including some braids, dreadlocks, extensions, and weaves,” she wrote.

Aguh’s goal isn’t merely to produce a new treatment for hair loss; she intends to find a cure.

“I’m a scientist but a person first,” she told the Baltimore Banner. “I want people to get better. If I’m retired from the hair clinic because no one has hair loss, that would be great.”