Nurses, as we understand the term, did not exist outside of religious orders in the United States during the Civil War, although the title did exist. It was expected that women would care for their own injured and ill family at home with, perhaps, house calls by a doctor and assistance from female relatives and close friends. The term nurse meant multiple things. A wet nurse, usually shortened to nurse, was a lactating woman hired to breastfeed an infant in a wealthy household. Nurse was also used as a term for a, usually poorly paid, and poorly educated, woman who cared for children. The third meaning was a recuperating patient who did miscellaneous tasks at the hospital. The fourth was a person paid to work in a hospital. The role was that of drudge. She did the most menial work, such as laundry and scrubbing floors. Hospitals were generally some place to be avoided if at all possible as care was generally much better at home. Those “nurses” had no education, and many of the hospitals included alcohol as part of their wages. During the American Civil War, women did much more to help the injured and ill combatants, and the possibility of a nursing profession gained a stronger foothold.

Women such as Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, saw a different role for women in hospitals. They envisioned women of good family, high moral standards, and equipped with proper training to care for the patients. Both Nightingale and Barton began their pioneering work during wars: Nightingale during the Crimean War (1853-1856) and Barton during the American Civil War (1861-1865). They saw both the need and the possibility for the development of a nursing profession. It is estimated that 3,000 paid nurses were employed during the American Civil War, and thousands more women volunteered their time. However, one category of women who nursed are not fully considered in those numbers. Both the Union and the Confederacy contracted for Black free women to work in hospitals. Some slave owners sent some of their enslaved women to work in hospitals, and the owner was paid for this. These were the more common ways Black women nursed during the Civil War, but we have two very different examples in Greene County.

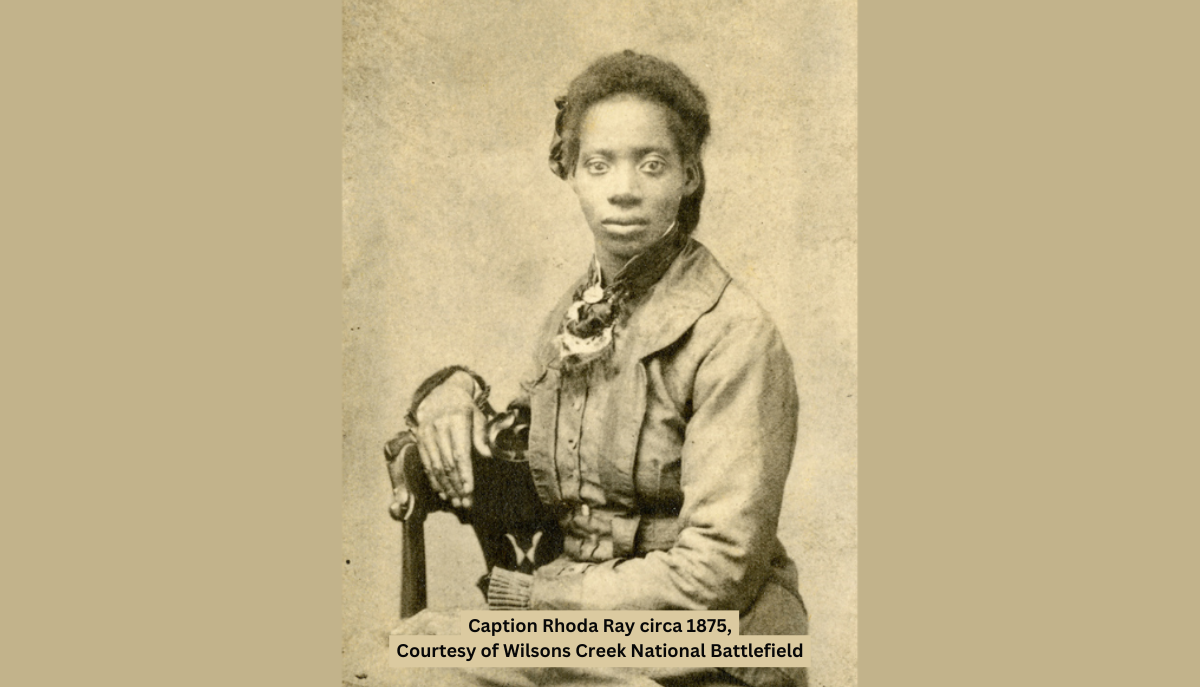

Rhoda Ray (c.1837-1897) and her children were owned by John Ray. The Ray farm was part of the land that the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (August 10, 1861) was fought on. Rhoda Ray and her children and John Ray’s wife, Roxanne, and her children sought shelter in the root cellar during the battle. Rhoda had been owned by Roxanne’s first husband. A fourteen-year-old Rhoda had been a gift upon their marriage. After the battle, the house was a Southern field hospital and Rhoda cared for the injured and dying soldiers. Her home was literally full of carnage. She was enslaved and may have had no choice about nursing these men and boys who were fighting to keep her and millions others enslaved, but she did it and in these most awful of conditions. She provided water and supplies to those who would not have done the same for her.

There is a perception that when the Union Army encountered slaves, they freed them. That is not necessarily so, especially before the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863). There is an account in the Union Provost Marshal Records of an enslaved woman owned by a man named Smith. She was taken from the Louisa Campbell house in Springfield because “Negro women are needed in the hospitals here” in September of 1862. This unnamed woman had no say in the matter. The Union Army needed Black women to work in the hospitals and they decided to take her.

By Joan Hampton-Porter

Curator, History Museum on the Square