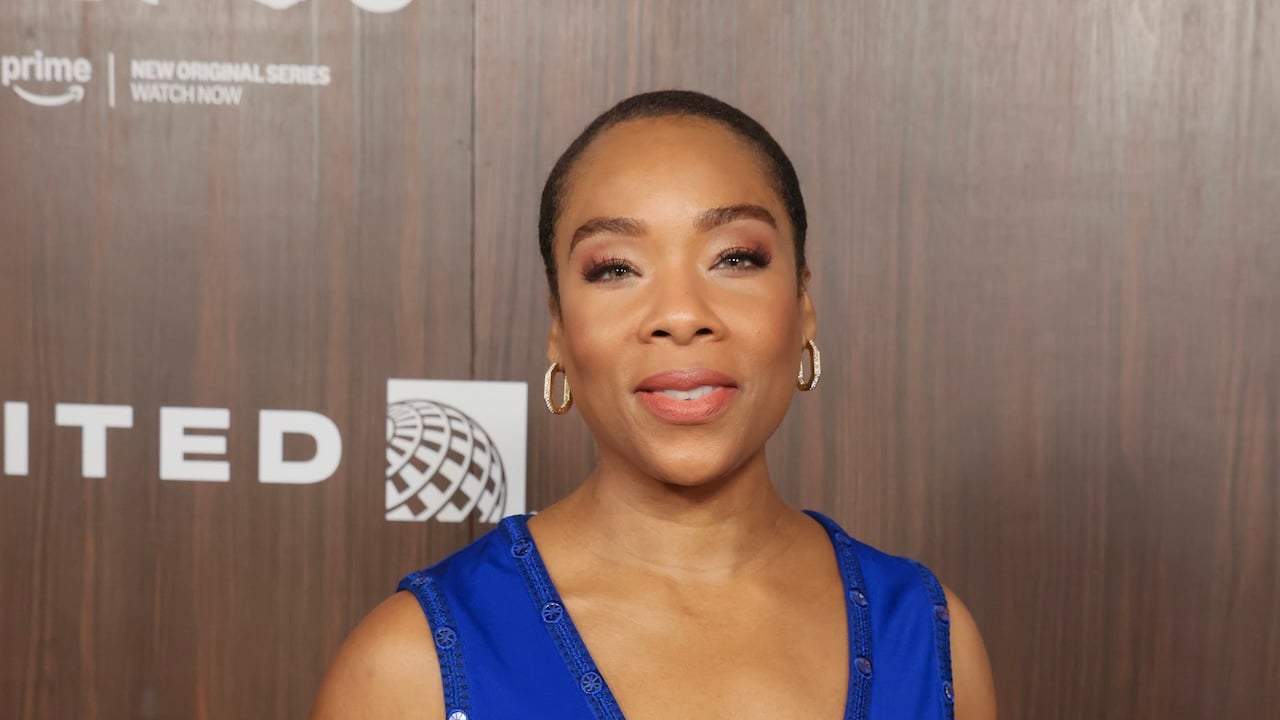

Award-winning producer Alisa Payne was living in Brooklyn when Hurricane Katrina was set to hit New Orleans in 2005, but her sister was a third-year law student at Tulane University.

Like many residents in New Orleans and the surrounding areas, Payne’s sister was planning to ride out the storm. Then, she was warned by a classmate’s mother, an executive at Entergy, to evacuate immediately.

“The problem was, my sister is able to get this intel, but the people in New Orleans, in Orleans Parish, did not get the evacuation notice until 36 hours before,” Payne said. “It is impossible when there’s one way in and one way out of the city to get all of those people out. It takes days and days, if not over a week, to evacuate an entire city.”

In “Katrina: Come Hell and High Water,” Spike Lee’s docuseries reflects on the natural disaster that turned into a manmade tragedy, 20 years later. Payne used her role as a producer to emphasize the structural reasons why New Orleans’ Black, elderly, and poor residents were most detrimentally affected by the storm and its aftermath.

Payne is the cofounder of the production company Message Pictures with Geeta Gandbhir and Sam Pollard, both of whom worked with Lee on his two previous projects about Hurricane Katrina, “When the Levees Broke” (2006) and “If God Is Willing and da Creek Don’t Rise” (2010). To commemorate the 20 years that have passed since Katrina, Netflix reached out to Pollard, who brought Message Pictures onto the project.

“Come Hell and High Water” in many ways is a continuation of the stories of the Katrina survivors Spike Lee interviewed in his previous documentaries. We hear again from public servants like former mayor Marc Morial, and beloved community members like Phyllis Montana-Leblanc, whom Lee called a “star” after she appeared in “When the Levees Broke.” But Payne said that this project is not supposed to make a “trilogy” of Lee’s two other works. She called “Come Hell and High Water” a “contemporized” version of the Katrina documentary for the next generation.

“People feel that they thought they knew the story. Twenty years later, we’re saying things like ‘systemic racism’ often. Using that language makes it very clear for people who, at the time, it wasn’t clear for.”

Payne’s career as a producer spans over 25 years, and some of her recent credits include the book adaptations of Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “Between the World and Me” for HBO and Dr. Ibram X. Kendi’s “Stamped from the Beginning” for Netflix. We also discuss one of her upcoming films, “The Perfect Neighbor,” which investigates the murder of a Florida woman named Ajike Owens through police bodycam footage, in the conversation below, which has been edited for clarity.

TheGrio: What was it like working on a project where many of the people had already been interviewed by Spike Lee previously and had shared their stories?

Alisa Payne: [Spike] and I had had a conversation about it, and he said, “I want to revisit them, because a lot of things have not changed for the better for these people.”

It was definitely important to say, 20 years later, these people are still affected. Twenty years later, infrastructure has not changed. Twenty years later, if something like this happened again, they could be in the same predicament. It was really important to talk to them. Phyllis Montana-Leblanc had been in the two previous pieces, but said this process and this team and seeing herself in this project has made her heal, finally, after 20 years.

TG: Do you know what kind of changes between then and now would have made her say that?

AP: I think it was calling a spade a spade behind the scenes. We had a lot of talk about whether to overtly talk about the institutional racism. My thought had always been that the racism was so overt, we should not be covert about it. And I think she was able to say the things very clearly. You know, “You could be the one-eyed, deaf, blind pirate and still see that this sh*t was racial.”

And I think it was being able to, one, tell her story, but two, be able to say that and to be affirmed by it, that really made a difference. You can think that you’re crazy because the narrative was spun otherwise.

TG: Going back and watching the previous documentaries, how did they inform the process of making this one?

AP: Spike and the team had relationships, but we were very clear that this was not supposed to be “Levees” part three. This is definitely a contemporized version with the new language that we have post-2020 and George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. So, this was supposed to be its own piece. And those other pieces were on HBO. This one is on Netflix, and so we brought on three different directors for that reason.

TG: When working on projects like “Stamped from the Beginning,” which is all about the creation of anti-Blackness and the definition of Blackness, how do you go about deciding how to execute such a large theme into something that an audience can watch in an hour and a half?

AP: I think it’s really about trying to figure out what the thesis is. The thesis of “Stamped from the Beginning” is: Whenever there is Black progress, there is a huge backlash. Dr. Kendi’s book is broken down into characters, but those characters are dealing with different time periods. And so we talked about what time periods we wanted to discuss.

In the thought of “Katrina,” it was about the thesis. Systemic racism and neglect led to Katrina and made it go from a natural disaster to the worst manmade disaster, and we needed to set the record straight. So if you start there, you start to figure out with the questions we ask and with the edits that we’re doing: Tonally, are we there? Visually, are we there?

TG: Do you find that there are differences or challenges between telling local stories, versus telling stories that connect different places?

AP: When you’re talking about something so wide as “Stamped from the Beginning,” we’re talking about 1452 to 2023. There was so much that hit the cutting room floor. The challenge is really to figure out what to include.

I think when you’re telling something that is hyperlocal, it’s both a challenge and an opportunity. For our project, “The Perfect Neighbor,” you can look at this as a neighborhood dispute, but it’s about so much more. It’s about how unjustified fear can lead to this. It’s also about “stand your ground” and how policy can lead to this person feeling emboldened to take this act. Even though it’s about one person killing another person, everyone has neighbors, everyone lives in a community, and should be an upstander, not a bystander. Everyone should try to get along and not be violent in community.

We all understand policies that can be harmful, and if we ignore policies that can be harmful, more policies come, and we have an authoritarian government that spreads from America to the world. In those pieces where it is about a small area, it’s always about making sure that it’s specific, but there’s a universality, where everybody can see themselves in it.

TG: “The Perfect Neighbor” relies on body cam footage over time. It’s less about bringing all these different pieces of media together. The storytelling is more linear.

AP: The attorneys did a FOIA request, a Freedom of Information Act, so that we could get the footage. But it’s police body camera footage, and nothing about that was linear. It was really difficult to try to even figure out which policemen were talking. The audio challenges on that piece was hell because they also have walkie-talkies competing with the sound.

And then also, police body cam footage is used often to surveillance Black and Brown communities. And so how do we use this, then, to flip that on its head? What we created was a community piece. It’s about this beautiful, multi-racial, multi-ethnic community with one dangerous outlier. And so I think in a lot of ways, it was harder to create “The Perfect Neighbor.”

TG: You’ve said that “Roots” informed your path as a producer.

AP: I was born in the 70s, but I grew up in the 80s, and in the summers, I would watch “Roots” replay. They would play it in the day when kids are home in New York City, and my brother and I would watch it. And it just really moved me to know the history. To see this cruelty, but also to see the resistance, the joy. They pointed out that Kunta Kinte had resisted from day one, and it informs my later work.

When we talk about “Stamped from the Beginning,” I say the same things that I learned from “Roots.” Black people resisted from day one. From the shores, they resisted. Enslaved people were creating families and lineage and trying to pass down the bits of their culture that they were forced to forget.

“Levees” also played a role, because it was so on the ground at the moment, and it was a counter-narrative. And it’s interesting, because when I did “Between the World and Me,” our director, Kamilah Forbes, was very clear that she wanted to do it within lockdown and during the pandemic. I lived up the street from Brooklyn Hospital, and there were people being put in freezers. And I had to figure out how to get actors, our crew, our staff, safely filming in six different cities. Before everybody was using Zoom, before we had vaccinations, we were out in the field in hazmat suits. Sixteen weeks and two days from the day I was hired to be the producer to when it was on air. I always say we were in pre-production, production, and post all at once.

Sometimes you put your body on the line because other people have done it before, to make sure that you can get something. We wanted it to affect the election. I never hope to make a project that quick again, but it was absolutely necessary.