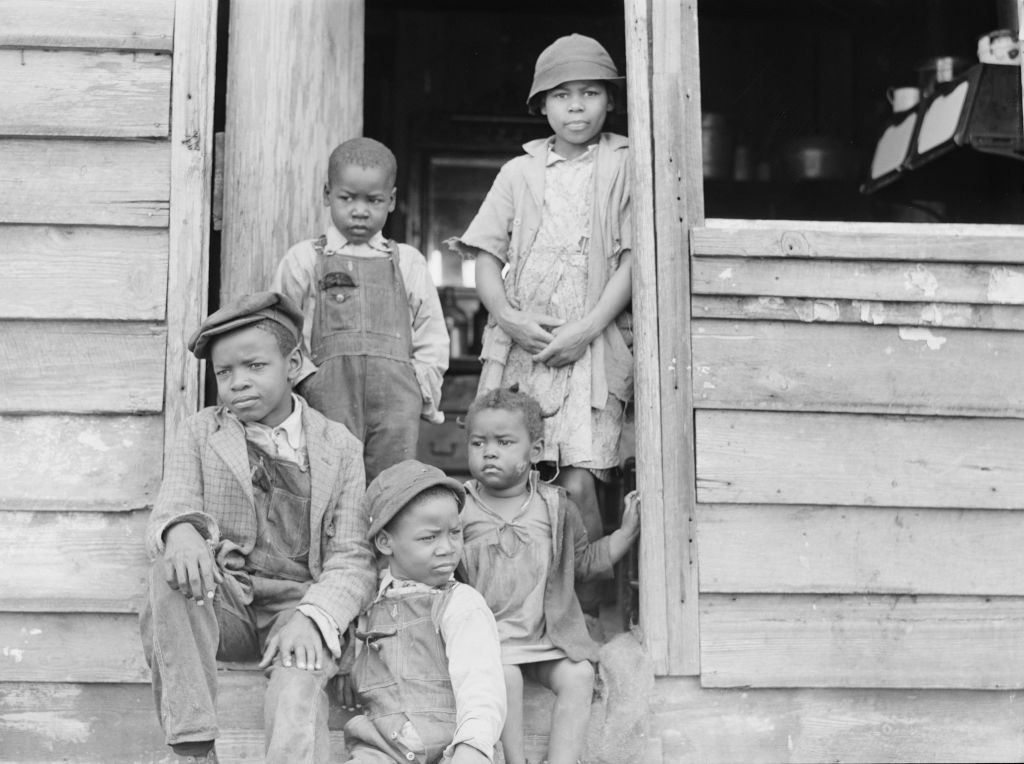

In 2019, ProPublica profiled Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels, two brothers from North Carolina who fought to keep their land out of the hands of white developers in accordance with the dying wish of their grandfather.

Mitchell Reels, who owned the land, did not leave a will but instead left the property to the pair as heirs’ property, a customary practice in the South.

Black land loss has been tied to this practice due to the assumption that even without a will the land will remain in the family. The reality, as the pair found out, is a lot more complicated than that. Davis and Reels eventually spent eight years behind bars after being found guilty of civil contempt stemming from their attempts to keep their family’s land in their hands.

A similar battle unfolded in 2012, as the Robinson family in Alabama used the same practice of heirs’ property. A stipulation in Alabama real estate law allowed anyone with any interest invested in a piece of land to sue the others to take control of the land via a sale.

According to Essence, the Robinson family was unaware that they even owned the land until they were notified of a lawsuit filed by James E. Deshler after he had purchased 1/15 of the family’s land. Like the Reels brothers, Michael Robinson’s grandfather, Joe Ely, had ceded the land to his heirs shortly before he passed away.

According to Ray Winbush, Morgan State University’s director of the Institute for Urban Research, the desire for these tracts of land owned by Black people, particularly Black men, was a motivating factor in lynchings.

Winbush told ProPublica, “There is this idea that most blacks were lynched because they did something untoward to a young woman. That’s not true. Most black men were lynched between 1890 and 1920 because whites wanted their land.”

David Cecelski, a historian of the North Carolina coastal area, also told ProPublica that there was a history of legal loopholes and tricks deployed against Black people in that area, saying, “You can’t talk to an African-American family who owned land in those counties and not find a story where they feel like the land was taken from them against their will, through legal trickery.”

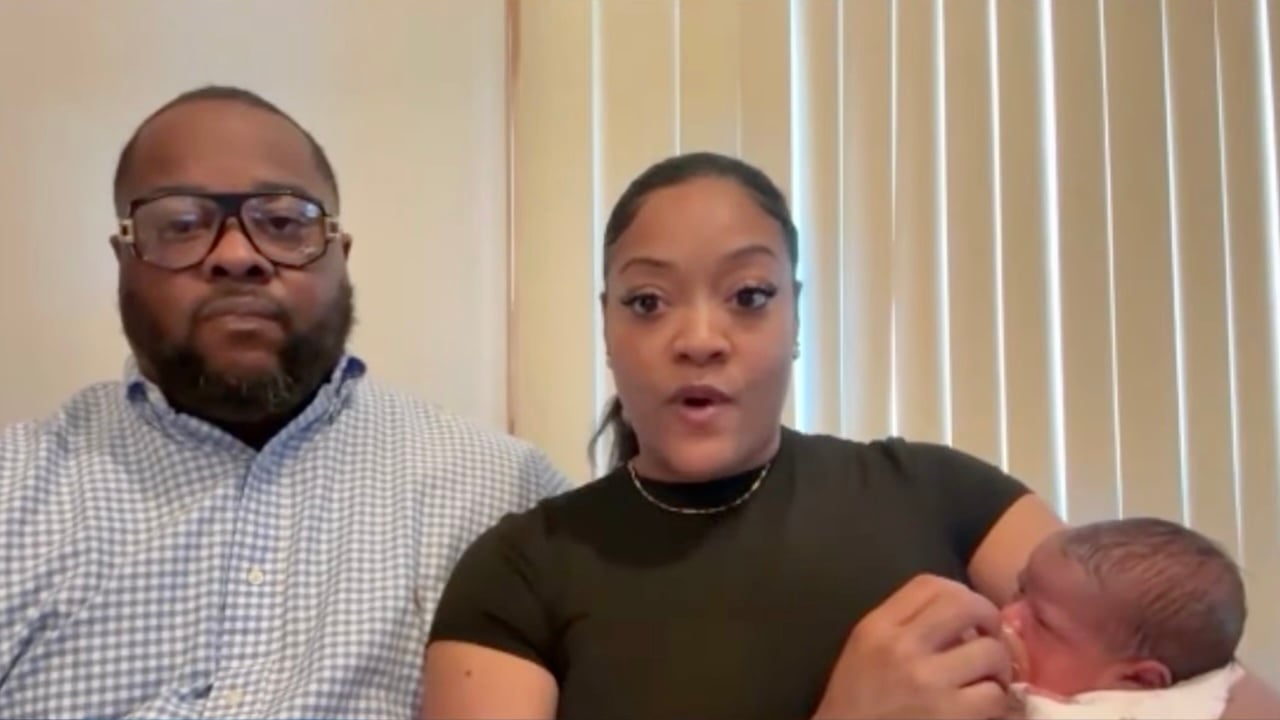

Legal trickery was deployed against the Robinson family in Alabama, but they found a way to fight back. Mitchell Robinson created a land retention committee composed of over 40 relatives which included his cousins, aunts, and siblings. This bought the family time as they fought the lawsuit brought on by Deshler.

Robinson told Essence his motivation was the future generations of his family. “I didn’t want three or four generations from now for some member of the family to say, ‘Didn’t we have over 100 acres of land?’” Robinson said. “I didn’t want someone to say, ‘That generation didn’t fight to keep the land in the family.’ So we adopted this motto of: Not on our watch.”

His determination, much like that of the Reels brothers, eventually paid dividends, as a judge threw out Deshler’s claim to the land in August 2023. The family took back the portion of the land Deshler once laid claim to a full 12 years after initiating the lawsuit.

“To me, it had even more meaning that people were enslaved on that land, and now we owned it, and we had the opportunity to change the narrative, the legacy, and the history on that land,” Robinson said.

“But it was so important for me to honor his legacy and the intent when he purchased that land. He could only dream or imagine where we are as people of color today. And I wanted to take the blood, sweat, and tears into that land and not let that die.”

RELATED CONTENT: L.A. County Officially Returns Ownership of Bruce Beach Resort To Heirs of Black Family