Written by: Joan Hampton-Porter

Curator, History Museum on the Square

Since prior to the American Revolution, Black Americans have fought in this country’s battles. Both free Blacks and those enslaved fought in the American Revolution. Some of the Black troops were armed soldiers, and others worked as teamsters or general laborers. There are a number of Revolutionary War Soldiers buried in Greene County, but none of them so identified are known to be Black. However, there may be Black unidentified American Revolution soldiers buried here.

There were local Black men who went to the Mexican-American War. One reference is in a Civil War memoir. Louisa McKinney wrote of Ab who went to the Mexican War with her grandfather, John Polk Campbell (founder of Springfield). It is unknown if he bore arms. She also stated Ab rescued her wounded uncle, Leonidas Campbell (a Confederate officer) under heavy gunfire during the Civil War Battle of Lexington. Officially, there were no Black Soldiers during the Mexican War, but there were those who fought.

After Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Black men were accepted into the Union forces. Approximately 3,700 Black Missouri soldiers served during the Civil War. This was the first time since the Revolution that Black Americans were officially able to serve.

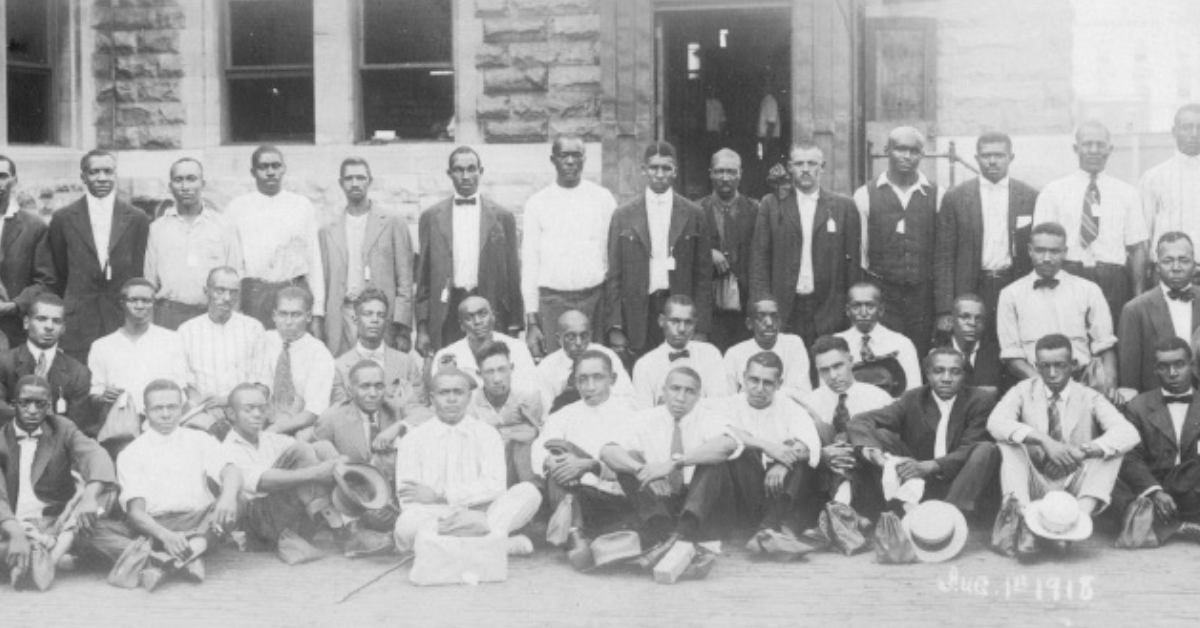

Many Black Greene County men served during WWI. Eighty-one are shown in the Honor Roll of Greene County. The most decorated man from Greene County during WWI was Myrl Billings. He was awarded two Croix de Guerre: France’s highest award for bravery. One was awarded as part of his regiment. The other was one of the 170 given to particular soldiers in that regiment for their valor. Billings was a member of the Harlem Hell1ighters (369th U.S. Infantry Regiment). It was composed of Black soldiers with white officers. Black officers were still a rarity. The 369th was the most decorated U.S. WWI regiment.

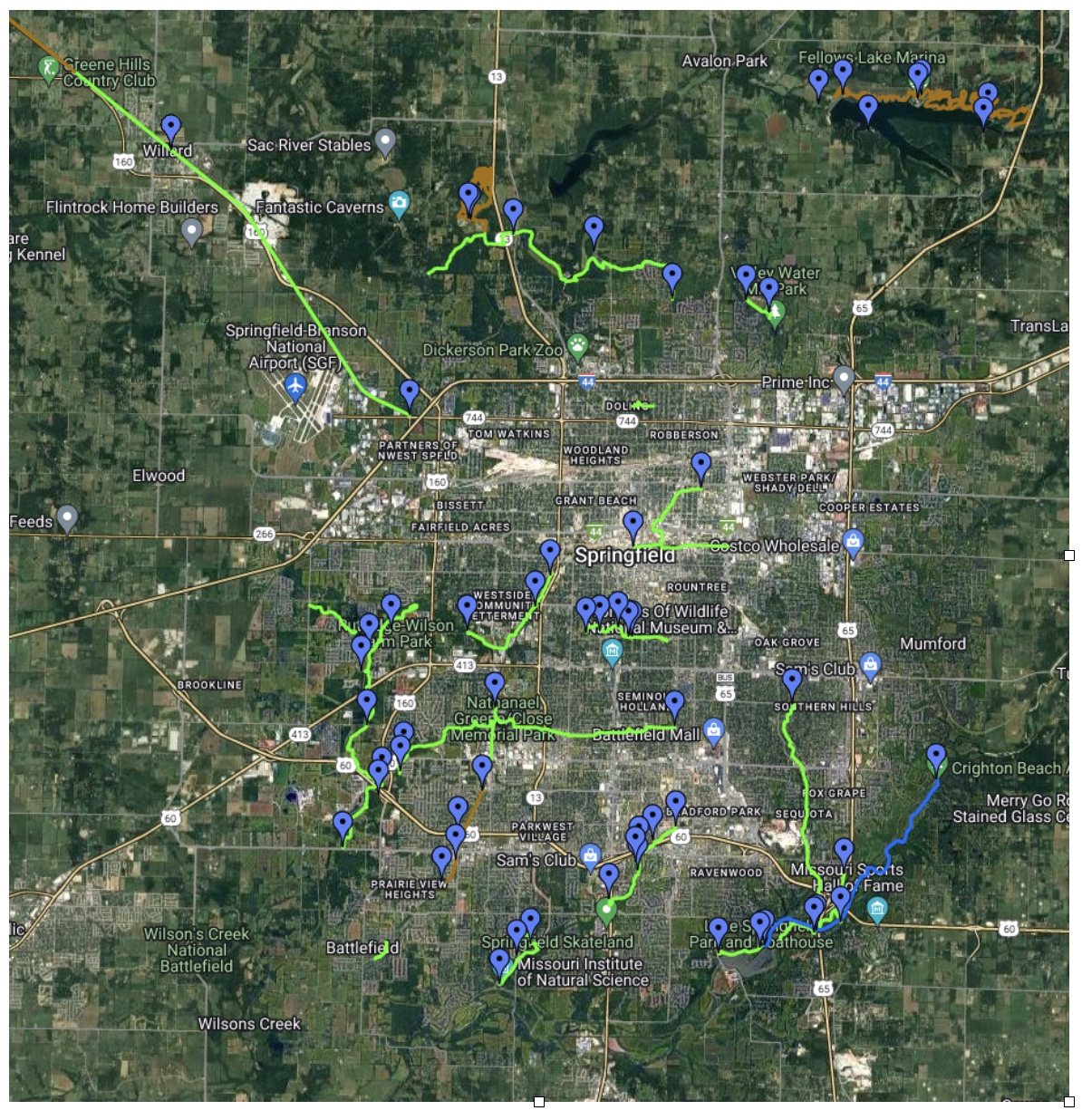

During World War 11, there were numerous ways Black soldiers could be connected to the area. They could be from here. They could be stationed or a patient at O’Reilly General Hospital, one of the ten largest military hospitals during WWII. They could have been passing through or on leave from Fort Leonard Wood. The military and the community were still segregated. For Black soldiers, there were few places where they were welcomed for a meal, a rest, or recreation. A contingent of soldiers took issue that not all of the Black soldiers would be able to get fed in the small area designated for Black Americans at the Harvey House located at the Frisco Passenger Depot. The soldiers, white and Black, tore down the wall so all could eat.

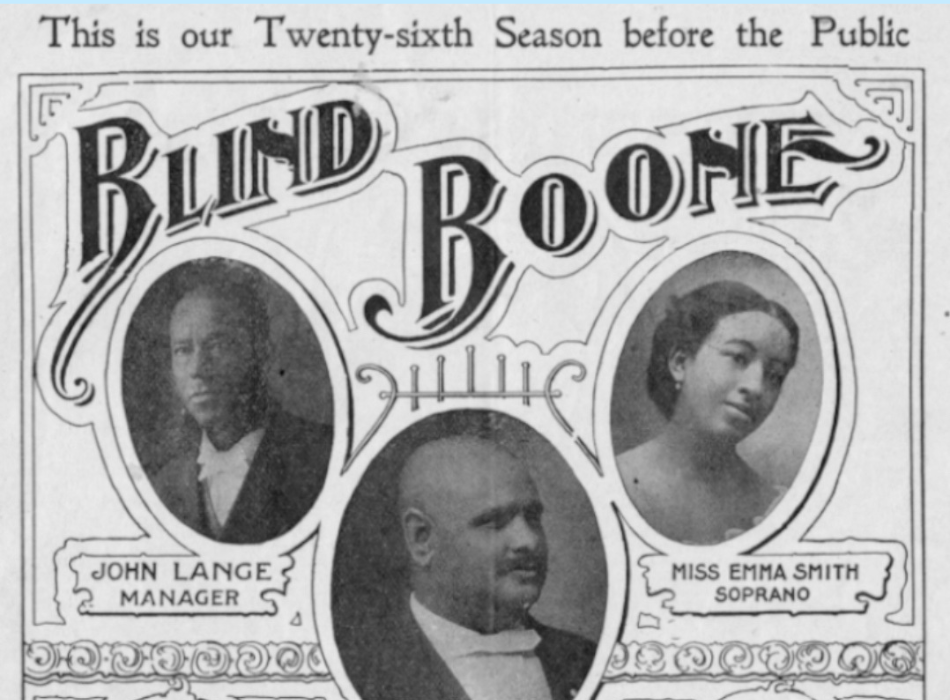

The U.S.O. organization started in 1941. In theory, all military personnel were to be welcome at all of the facilities regardless of race, but it was rarely the practice. A Black U.S.O. did not open locally until 1943. However, that does not mean that the need was not recognized and addressed. A “Negro Service Club” was started by local individuals so that Black service people could sleep (up to 26 soldiers a night), relax, and enjoy entertainment. It served 500 to 1000 people a month. It also aided the mothers and wives of service personnel. When a grieving mother would have had to attend her son’s funeral alone, volunteers joined her. In 1943, the U.S.O. took over the club. Most of the volunteers were the same, but there was better funding. Two Lincoln teachers were in charge of the hostesses: Olive Decatur (president, senior hostess club), and Cordia Penn (sponsor, junior club).

After he had tried and failed to get Congress to do so, President Harry Truman used an executive order to direct the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces in 1948. In 1951, officers from Fort Leonard Wood visited Springfield’s dining, dancing, and drinking establishments to find out which were currently serving Black servicemen and to issue a warning that if the establishments were not open to service people of all races, the business would be banned. According to a newspaper article, most of the businesses refused to cooperate with the rule. By the end of the Korean War in 1953, the majority of the military was desegregated.

Black people have served and continue to serve with distinction in the military in every U.S. War, even before the United States was its own country.