Written by: Joan Hampton-Porter

Curator, History Museum on the Square

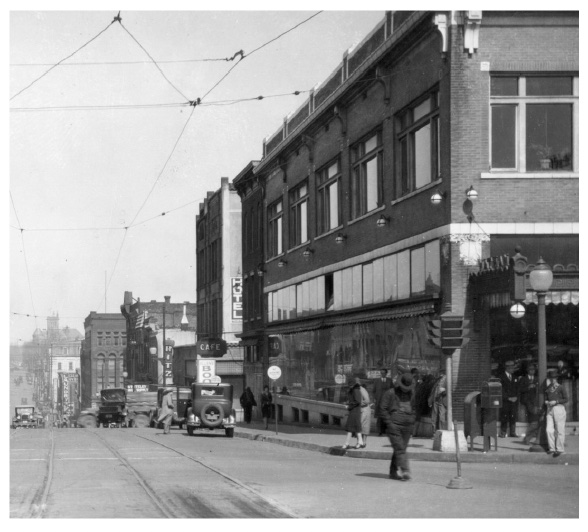

From the 1910s through the 1930s there were a few exclusively Black theaters in Springfield. The Springfield Greene County Library has a listing for an unnamed Black theater at Phelps and Jefferson around 1911. The Ritz was located in the 300 block of Boonville in the 1920s. The Palace, location unknown, boasted an electric piano and vaudeville offerings in addition to movies.

From the 1930s to the 1960s, there was one indoor movie theater that Black patrons could attend in Springfield: the Landers. The Landers had a second balcony for Black patrons only reachable by a staircase from an alley. The balcony was open only on specific nights. It was discontinued sometime during the Korean War. Homer Boyd recalled years later his experience when he was fresh back from fighting for freedom as a member of the United States Army in Korea. He wanted to see a movie and was prepared to sit on the second balcony, only to find out that even that was now denied him. Over 60 years later, I could still hear the hurt in his voice about how he was good enough to fight and potentially die for this country, but he couldn’t even see a movie in his hometown. There is an extra bitter irony to Boyd being turned away. A few years before, as a member of the Philharmonics, he helped desegregate the Southwest Missouri State University Field House. The Philharmonics won the Horace Heidt Youth Opportunity Showcase, a television competition, twice and toured with the show. Horace Heidt refused to allow the show to appear at segregated or all white venues. Prior to this performance, Black patrons were not admitted to the Field House. The Philharmonics, a men’s vocal ensemble, became very well known as they were regulars on the Ozarks Jubilee, a nationwide country music show.

Sometime between 1953 and 1958, Black patrons were again able to see movies at the Landers. In September 1958, the Springfield Chamber of Commerce commissioned a survey to determine which restaurants, motels/hotels, and theaters would serve Black customers and if there were stipulations. There were six theaters surveyed: Fox, Gillioz, Tower, Sunset Drive-in, Springfield Drive-in, and Landers. The Fox, Gillioz, and Tower did not admit Black theatergoers at any time. The Landers admitted Black theatergoers only to the second balcony and only on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. Only the outside theaters, the Sunset and Springfield drive-in theaters, admitted Black customers on an equal footing with white customers.

In theory, the 1964 Civil Rights Act eliminated discrimination in public accommodations, including restaurants, motels/hotels, and theaters, but that doesn’t mean that things changed everywhere in practice, at least not without a push. Around the same time, Denny Whayne, who later paved the way as the first Black person to be a Springfield City Councilman in almost 100 years, was spearheading the protests that led to the desegregation of the Tower. 1964 (sixty years) probably seems like a long time ago, but it isn’t. It is a mere two generations since the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex(gender), national origin, or religion.