By Joan Hampton-Porter Curator, History Museum on the Square

The Federal Writer’s Project (1936-1938) recorded the personal narratives of over 2,000 former slaves from seventeen states as part of the Works Project Administration during the Great Depression. The narratives from Missouri are documented at the Library of Congress and can be read at www.locgov/item/mesn100/. The only one recorded from Springfield was Filmore Hancock’s. Readers are advised that they may find disturbing some descriptions and terms in the original document. The information below combines material from Hancock’s narrative and other sources.

Hancock’s grandmother, name unknown, was given on the day of her birth to her one-year old mistress, Louisa. When Louisa was grown, she married John Hancock. He owned twenty-one slaves and she owned eleven: including Fil’s grandmother and most of her descendants. John was not allowed to “discipline” his wife’s slaves. Hancock owned over 1,000 acres between Springfield and Strafford with 375 acres under cultivation with corn, oats, wheat, rye and clover.

Fil’s father, name unknown, was enslaved by the Langston family. Children born to female slaves became the property of the mother’s owner. Fil’s maternal grandmother was the cook for the Hancocks, and after his mother died, he was largely raised in the big house.

Fil’s grandmother’s first child, Joe, was given to the mistress’s first child Bill. When Joe was grown John tried to whip him, despite Joe not being his slave. Joe broke the hold and ran. As a result, John sold Joe as well as one of his own slaves, Jane, to Mr. Dokes, a slave trader who sold in St. Louis. Mr. Fisher, one of the neighbors, rode from Strafford to Springfield to inform Bill. Fisher told Bill that if he bought both of them, Fisher would then buy Jane from him for his own male slave. They caught up with Dokes on the road to Rolla and both were purchased. Jane went to Fisher. Joe, however, did not go back to the farm as Bill’s father refused to have him on property, except for occasional visits to see his mother. Joe was hired out to a Springfield blacksmith. Fil described Joe as being extremely grateful that Bill bought him back. If he had been sold in St. Louis, he likely would have never seen his family again and he could have been in worse conditions.

Fil recalled that some owners were much more liberal with passes than others and explained how slaves met in secret in the woods during the summers for religious services, but generally did not bring the children. He remembered his first pair of boots. Boots were generally not given to children, only to older workers, but he was given a pair while still a child and was allowed to go to the neighboring Massey property to show his aunt, who was enslaved there.

Fil recounted experiences with soldiers. He remembered seeing General Lyon and his troops on the way to the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, as well as his mistress taking him and the other Black children to see Lyon’s body on its transport east. Despite the Hancocks being Confederate sympathizers with sons serving in the Confederate army, Confederate General Marmaduke’s men stole everything from the spring house, used to keep cool milk, butter, and cheese. Soldiers also took so much water from the spring that it was practically dry. Fil also recalled that he and some of the other Black children were scared by the Union soldiers and hid out all night. The most significant time was when Union soldiers liberated him from the farm and took him to Yellville, Arkansas. He was kept for a time at the camp but then had to fend for himself. He would have been 10 or 11 years old and over 100 miles from everyone and everything he knew.

As an adult, Fil was a hotel porter and barber. He wanted to be buried with his parents in the Union Campground Cemetery in Springfield but was buried in Rolla, where he lived at the time of his death. The interviewer noted that Fil was known for his performances with the tambourine, including appearing to great acclaim at the Folk Arts Festival in Rolla. Fil gave an impactful quotation regarding Black and white relations and innate talent. The quotation has been adjusted to standard spelling as the original was an outside person’s attempt to record dialect. “You know it’s a funny thing, the white folks took everything from us n******, even try to take our old songs and have them on the radio. We n****** say the white folks take everything, this, that, and the other, but what we got is just natural talent born to us.”

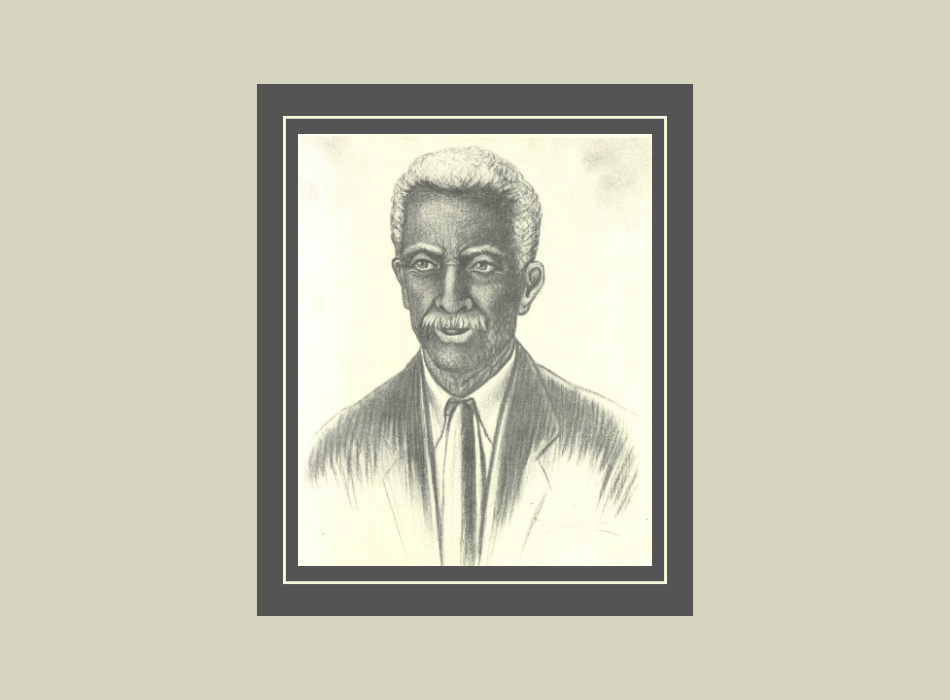

Photo: Filmore Hancock was drawn by Lennis Broadfoot and the image was included in his 1944 publication Pioneers of the Ozarks. Broadfoot spelled Hancock’s name as “Phil/Phillip” but his tombstone and the slave narrative list him as “Fil/Filmore.” The Harlin Museum in West Plains which holds the very extensive Broadfoot collection gave permission for the use of the image.