To earn his freedom, 15-year-old Cayden Gillespie had to complete three school assignments a day. But school had gone virtual for Cayden and other incarcerated young people in Florida. And sometimes, he didn’t understand it.

One day last summer, he kept failing an online pre-algebra test. There were too many words to read. He didn’t know how to find the value of x. And there were no math teachers to show him.

“I couldn’t figure it out, and it kept failing me,” Cayden says. He asked the adult supervising the classroom for help. “She didn’t understand either.”

Frustrated, Cayden picked up his metal desk and threw it against the wall. A security guard radioed the office for help.

Cayden worried what might happen next.

A respected online school — and a rocky rollout

No matter the offense, states must educate students in juvenile detention. It’s a complicated challenge, no doubt — and success stories are scarce.

Struggling to educate its more than 1,000 students in long-term confinement, Florida embarked last year on a risky experiment. Despite strong evidence that online learning failed many students during the pandemic, Florida juvenile justice leaders adopted the approach for 10- to 21-year-olds sentenced to residential commitment centers for offenses including theft, assault and drug abuse.

The Florida Virtual School is one of the nation’s largest and oldest online school systems. Adopting it in Florida’s residential commitment facilities would bring more rigorous, uniform standards and tailored classes, officials argued. And students could continue in the online school, the theory went, once they leave detention, since incarcerated youth often struggle to reintegrate into their local public schools.

But students, parents, staff, and outside providers say the online learning has been disastrous, especially since students on average spend seven to 11 months in residential commitment. Not only are students struggling to learn online, their frustration with virtual school is sometimes leading them to get into more trouble — and thus extending their stay.

In embracing Florida Virtual School, the residential commitment centers stopped providing in-person teachers for each subject, relying instead on online faculty. The adults left to supervise classrooms rarely can answer questions or offer assistance, students say.

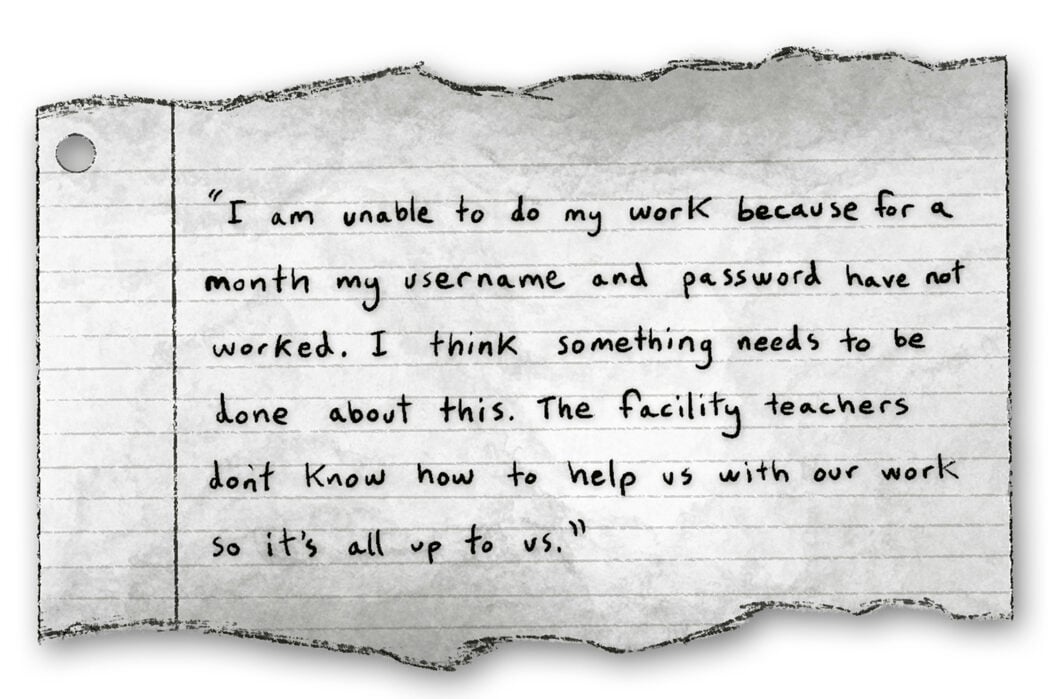

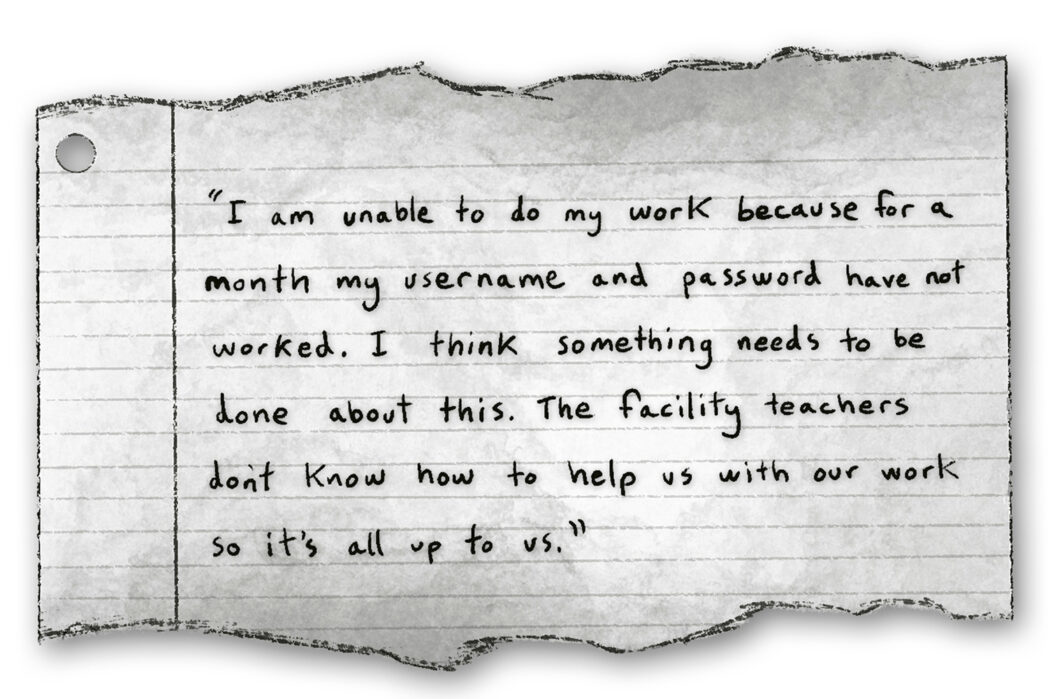

A dozen letters from incarcerated students, written to lawmakers and obtained by The Associated Press, describe online schoolwork that’s hard to access or understand — with little support from in-person or online staff.

“Dear Law maker, I really be trying to do my work so I won’t be getting in trouble but I don’t be understanding the work,” wrote one student. “They don’t really hands on help me.”

When Cayden arrived at the Orlando Youth Academy in January 2024, after four months in juvenile detention waiting for a bed in long-term confinement, he felt disoriented. He and his family had been told he would be placed at a residential center near their Gainesville home so they could visit on the weekends. The judge had recommended 30 days in the residential center — called “treatment” — after Cayden pleaded guilty to two fraud felonies for using stolen credit cards, including one belonging to his parents.

As he sat in a metal chair at his new case manager’s desk, she described the routine and expectations of what she called “the program.” He’d attend more than six hours of school a day and therapy five days a week, including with his parents over Zoom. None of this surprised Cayden.

But then she said something that got his attention. “The program” would likely last six to nine months.

Panicked, he asked to call his mother.

A monthslong stay in ‘a teenage jail’

Robyn Gillespie stepped outside the Gainesville McDonald’s she managed when she saw a call from the Department of Juvenile Justice. That can’t be true, she said, when Cayden told her his sentence was far longer than expected.

So Cayden, still sitting next to his case manager, put down the phone and asked her again: Ma’am, you said six to nine months, right?

Gillespie hung up and cried. “They wouldn’t understand him,” she remembers thinking.

Gillespie’s husband, Kenny Roach, initially thought going to juvenile detention could help Cayden, who had grown out of control. The family had recently moved to Florida to care for aging relatives, but Cayden’s beloved older brother decided to return to Virginia, where they’d lived before.

Cayden, who has autism, struggled being in a new place without his brother. He began leaving the house in the evening with neighborhood teens when the parents worked late. That led to shoplifting and, eventually, credit-card fraud. Roach and Gillespie pressed charges against their son.

“He really needs to get a week in a detention home,” Roach thought. As a youth, he himself had gone to juvenile detention twice, for as long as two weeks, and credited it for a life turnaround. “I thought it would be a learning experience.”

When he learned Cayden’s time in the juvenile detention system would last much longer, he was in shock.

“Good lord, what do they hope to accomplish? A kid his age, with his diagnosis?” Roach remembers thinking. “That’s like being in a teenage jail.”

Life in custody: Not much privacy, avoiding a ‘level freeze’

Cayden and the other detainees inside Orlando Youth Academy woke up every day at 6 a.m. and cleaned their cells. Only when they passed inspection could they enter the common area.

Each detained youth had a toilet in their cell. For privacy, they were encouraged to lodge notebook paper into the door jamb to cover the narrow vertical window in their doors.

Phone calls with their parents were monitored. At family visits, Cayden’s parents couldn’t get too close or hug him more than once at the beginning and end, to prevent visitors from sharing contraband with the teens.

To relax, Cayden would lie on his stomach on his plastic-covered mattress and draw and write. He developed a Pokemon-inspired story about a hero named One — the only time he allowed his mind to wander away from Orlando Youth Academy.

When the teens got in trouble, they had to go to bed early — 5:30 p.m. — and skip playing cards or watching TV, some of the only downtime they got. But the real punishment was called a “level freeze.” When a detainee got in trouble for fighting, damaging property, not attending therapy or refusing to log into online school, they stopped making progress toward release.

Online school lacked special education supports

Before Orlando Youth Academy and Florida’s other commitment centers adopted virtual learning in July 2024, Cayden’s main source of stress was the other students. They antagonized Cayden until he exploded. Therapists and staff coached him to avoid these situations.

School wasn’t a source of stress or conflict. Four teachers from the local schools came to their portable classroom and lectured students ages 12 to 18 from the front of the room.

Cayden came to the program midway through what should have been his seventh grade year. But after assessing him, the teachers placed Cayden in sixth grade.

When the state adopted virtual schooling, it was partly trying to meet the needs of students across different ages and abilities. But Cayden felt some of the new classes were too advanced, and he didn’t receive help he needed to do the work.

The complaints from other Florida detainees are similar.

“My zoom teachers they never email me back or try to help me with my work. It’s like they think we’re normal kids,” one youth wrote in a letter to Florida lawmakers. “Half of us don’t even know what we’re looking at.”

Under Cayden’s special education plan, which federal law requires detention center schools to follow, he’s entitled to receive assistance reading long texts. But he didn’t receive it after the virtual school started.

Florida Virtual School wouldn’t comment on Cayden’s case, citing privacy concerns. Within their school for students in long-term confinement, “every student with a disability receives specially designed instruction, support, and accommodations comparable to those listed in the student’s Individualized Education Plan (IEP),” says Robin Winder, chief academic officer of Florida Virtual School.

The instructor assigned to help Cayden and more than a dozen other students with their online work was overwhelmed by the students’ needs, Cayden says. Three different people held that job during the nine months he attended virtual school inside Orlando Youth Academy.

When Cayden threw the desk out of frustration with the new online learning program, he received a “level freeze” of three to five days, essentially extending his time at the residential commitment center.

It’s easy to tumble into ‘dead time’

Internal documents obtained by The Associated Press, plus interviews with parents, staff and outside specialists, show staff have recommended or given level freezes when students have broken laptops, refused to log into Zoom and even sent an email to ask for help initiating an online class. And when students don’t participate in virtual school, the department’s written protocol calls for taking away points they earn toward getting out.

“Students who have their heads down will be prompted by the teacher no more than two times to sit up and participate,” reads the Classroom Behavior Management Plan for Florida’s juvenile justice schools.

The first time Xavier Nicoll, 15, broke a laptop at his residential commitment center in Miami, it was because an online teacher wouldn’t respond to his questions, according to his grandmother, Julie, who has raised him. He was arrested and sent to a different detention center to face charges. The three weeks he spent there didn’t count toward his overall sentence because he can’t receive “treatment” there. Detainees call it “dead time.”

Once back at the residential center, he broke another laptop, his grandmother says, because a teen dared him to. Back he went to county detention and court for more dead time. Then, in January, when the in-person class supervisor wouldn’t help him get into a locked online assignment, he broke a third, says Julie Nicoll.

Xavier was initially meant to be held for six to nine months after breaking into a vape store. He’s now on track to be confined at least 28 months.

He’s grown at least five inches in detention — and gone through puberty. Yet in school, Nicoll said in April, he was making no progress. “He went in as an eighth grader and is still an eighth grader — and failing,” Nicoll said.

Xavier’s March report card showed he was earning a 34% in Civics and Career Planning, 12% in Pre-Algebra, 13% in Comprehensive Science and 58% in Language Arts.

Nicoll has complained that her grandson, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, hasn’t been receiving special education services. The Department of Juvenile Justice and Florida Virtual School have canceled multiple meetings to discuss his education plan because Xavier keeps getting arrested and sent for dead time.

“He’s trapped,” says Nicoll. “No matter what we do, we can’t seem to get him out.”

Nicoll and her husband have spent more than $20,000 in legal fees trying to win his release. They argue untreated brain inflammation due to mold exposure in detention, plus his disability, make it impossible for him to control his frustration during online school.

In May, Xavier was arrested a fourth time. After turning in an assignment, he realized he’d made a mistake and asked the in-class supervisor to return it. The supervisor wouldn’t give back his work, and he broke another laptop.

Xavier pleaded guilty in August to two felonies for breaking laptops. “They’re setting him up to go into the community a failure,” said Nicoll.

It’s unclear how many students are getting in trouble or extending their time because of behavior during virtual school. Arrests inside residential centers increased slightly in the first nine months after the department adopted virtual school, compared with the same period during the previous year. An analysis of publicly available data shows staff use of verbal and physical interventions has also risen slightly, to 2.4 physical or verbal interventions per 100 days from 1.8 interventions the previous year.

The total number of youth in Florida’s residential commitment centers increased to 1,388 in June, the latest data reported by the state, up 177 since July 2024, when the department adopted virtual instruction. That could indicate detainees are staying in confinement longer.

“Correlation does not equal causation,” responded Amanda Slama, a Department of Juvenile Justice spokeswoman. “Other contributing factors could explain an increase in arrests if there is one.”

Since December, the department has ignored or refused AP requests to visit juvenile confinement, speak to officials and release anonymized exit documents for students leaving commitment centers.

Not all students are getting in trouble during online schooling, but that doesn’t mean they’re learning. Jalen Wilkinson, 17, received punishment during detention for fighting, but his father was unaware of punishment related to school.

But when school went online in July 2024, Jalen started complaining that there weren’t enough adults to help students with the virtual program. School, he says, is basically free time.

Jalen has been especially frustrated that he couldn’t complete his GED while confined — even though Florida Virtual School leaders say they’ve made it easier for detainees to take the exam.

He was released in July. His father, John Terry, worries the time locked up was a waste and Jalen will struggle to re-enter high school and graduate. “There’s no rehabilitation whatsoever.”

Cayden is still trying to restart school

In March, shackled with an ankle monitor, Cayden Gillespie finally left Orlando Youth Academy. The six to nine months his case manager predicted turned into 15. Between that and the “dead time” waiting for a residential center bed, he was detained 19 months.

Through therapy at the residential center, Cayden learned how to recognize his anger building and to take a break. His parents say the family therapy helped them better understand Cayden’s needs and helped them all communicate.

“But the school part,” Robyn Gillespie says, “that was a disaster.”

Gillespie, her husband and Cayden are still trying to understand the consequences of going so long without proper schooling. Initially, they thought he’d go to the local public middle school, but the school said, at 15, he’s too old. This spring, they tried to sign him up for Florida Virtual School, the same program he did in custody. Indeed, this was one of the arguments the state made for using virtual school inside confinement. But Robyn Gillespie says Florida Virtual told them he couldn’t join so late in the year.

Asked about Cayden’s case, Florida Virtual said all students “released from a facility receive one-on-one support from an FLVS transition specialist.”

But Cayden’s family said they were never offered transition help or told how he could continue where he left off in detention.

The best option, they’ve been told by the local school district, is a charter school, where he can make up coursework quickly.

“That’s the kind of place where they dismiss you if you don’t show up on time,” says Robyn Gillespie. “And there’s no transportation. I’m just not sure that’s going to work well for our family.”

The terms of Cayden’s probation require him to attend school or face confinement again. He starts at the charter school later this month. Says Gillespie: “He has to be in school.”