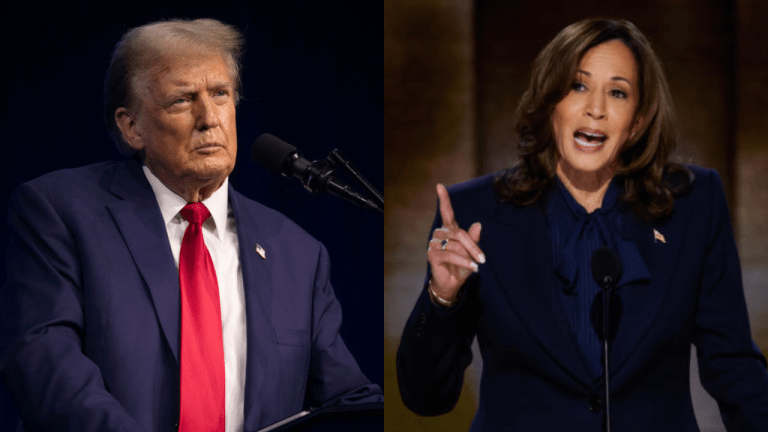

A Republican national organization shockingly and inaccurately argued that Vice President Kamala Harris is ineligible to run for president, citing a slavery-era Supreme Court decision that ruled Black people were not U.S. citizens.

The National Federation of Republican Assemblies makes the argument in a newly adopted resolution, citing the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford case, among others, which ruled at the time that enslaved Black people were ineligible for U.S. citizenship.

The NFRA, whose convention Donald Trump attended as a presidential candidate in 2015, says in its resolution that states and political parties have “ignored” the “fundamental” qualifications for president by allowing candidates like Harris, the Democratic presidential nominee, to run for the Oval Office.

The group cites that Harris’ “parents were not American citizens at the time of their birth,” including the names of Republican 2024 presidential candidates Nikki Haley and Vivek Ramaswamy.

The NFRA resolution states: “Ignoring Presidential qualifications undermines the foundation of Constitutional legality for governance and security for the United States by allowing unqualified candidates to run in Primary State contests.”

The National Federation of Republican Assemblies’ claims are false. Harris is a natural-born citizen of the United States. The former U.S. senator, California state attorney general, and San Francisco district attorney was born in Oakland.

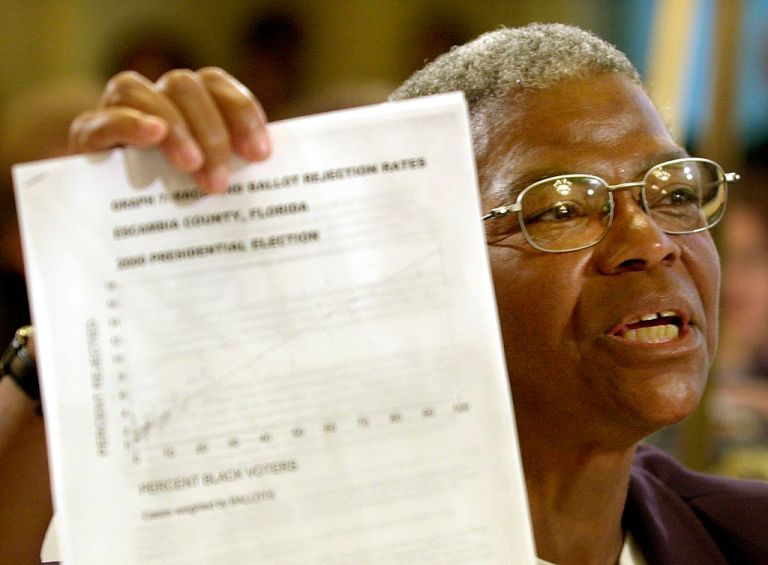

As far as the Republican organization’s attempt to evoke the Dred Scott decision in its attempt to delegitimize Harris’ eligibility for president, Dr. Mary Frances Berry, a professor emerita of history at the University of Pennsylvania, tells theGrio that the SCOTUS ruling has “no authority” in the U.S. Constitution as it was overturned by the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, and 14th amendment, which established equal protections for U.S. citizenship, in 1864 and 1868, respectively.

“They are putting this out there because it has been a long-held view of people of that ilk on the conservative side that Dred Scott defined [African-Americans],” said Dr. Berry, who is the former chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “The Dred Scott case does say … that Blacks, Negroes, could never be citizens. The Constitution didn’t intend for us to be.”

She added, “The Dred Scott case accurately expressed what many people in the country at the time who were slaveholders believed.”

In the 1857 case, Dred Scott, a Black man in Missouri, sued the state in St. Louis Circuit Court for his and his wife’s freedom. According to the National Archives, the Scotts lived with their enslaver in Wisconsin territory, where slavery was outlawed. However, they were later returned to a slave state. Scott ultimately lost his case for his freedom, resulting in an explosive debate about the issue of slavery.

Dr. Berry points out that Dred Scott v. Sandford has long been viewed by legal scholars as the Supreme Court’s worst decision.

“Legal scholars know that it was a political decision and that it was designed to uphold the institution of slavery,” she explained.

Berry said of the National Federation of Republican Assemblies’ resolution: “We should all be embarrassed by the existence of anyone reaching back to the history of slavery and coming up with the Dred Scott decision and dragging it into the conversation.”

She added, “We moved years beyond that and had to fight a bloody civil war and do all kinds of things since then in order to try to get over that scar of the national escutcheon.”

The false claims about Harris’ racial identity and citizenship are not a new development in the 2024 presidential election cycle, nor is it the first time her eligibility has been called into question.

Last month during an interview at the National Association of Black Journalists convention, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump questioned whether Harris, the daughter of an Indian mother and Jamaican father, was actually Black.

“I didn’t know she was Black until a number of years ago when she happened to turn Black,” said Trump. “Now she wants to be known as Black. So I don’t know, is she Indian, or is she Black?”

As president in 2020, Trump also questioned then-vice presidential candidate Harris’ citizenship. He suggested that Harris possibly “doesn’t meet the requirements” to serve as vice president.

Trump infamously led a false and racist “birther” conspiracy theory campaign against Barack Obama, America’s first Black president. He and others falsely suggested that Obama was not born in the United States, despite being born in Hawaii to a mother who was born and raised in Kansas.

Trump and other Republicans have also targeted the issue of birthright citizenship altogether. In 2018, he threatened to abolish birthright citizenship through an executive order and renewed the call in the 2024 election cycle.

Joel Payne, a Democratic strategist, said the false claims about Harris’ citizenship and racial identity are “not worth a rebuttal because it is baseless.”

He told theGrio, “The Harris campaign has been smart to not engage here because it’s pretty clear” that Trump and Republicans’ “entire offering to the American public is tired and played out.”

Payne argued that Trump’s coalition of supporters is “dependent” on voters who believe “conspiracy theories” and false legal notions like those outlined by the NFRA, which he described as a “sad state of affairs.”

“It explains why [Trump] is so permissive when it comes to people who are clearly operating way outside of the mainstream with extremist and bigoted rhetoric, not just about Kamala Harris, but just generally speaking,” said Payne. “These people clearly do not respect key elements of the American story.”

Citing Harris’ campaign slogan, “We’re not going back,” Payne said the drumming up of the 1857 Dred Scott case and the issue of citizenship for Black people “fits nicely” into the Democratic nominee’s message to voters.

“They want to go back to a time when less people had rights, and less people had self-determination. These are serious considerations that people have to make when they’re thinking about who they’re voting for and what their vote means,” he said. “There’s the political piece of it, and then there is just a cultural component of what are you giving permission to?”